From shame to success

Photo: Morten Gjerstad

Photo: Morten Gjerstad

Photo: Morten Gjerstad

Photo: Morten Gjerstad

Roald Sandal’s challenges were the starting point for the world’s first dyslexia-friendly workplace. The petroleum industry is now following up.

- Working environment

This is the story of a man who felt he was in the world’s best job – until he had enough of the steadily growing demands for form-filling and other forms of writing.

It is also the story of HSE vice president Harald Eik, who met Sandal with curiosity and a desire to help.

Of Arild Magnussen, Sandal’s colleague and friend, who joined him in clearing the way for openness about challenges which many industrial workers struggle with.

Of a strong trade union, which drove forward change together with the company.

And of Sandal’s daughter, Hanne.

Nickel

A long, narrow, zebra-striped pedestrian walkway crosses the big square from the main gate to the door of the administration block at Glencore Nikkelverk in Kristiansand.

Rounding the corner, a forklift truck stops for a group of workers, eye contact is established with the driver, and the pedestrians cross. Traffic safety is important in a complex with many buildings and sharp bends.

Nickel has been produced at the works just outside the city centre since 1910. And this major industrial workplace in southern Norway has always been conscious of its social responsibility.

It was and aims to continue being the place for those with able hands who have failed for various reasons to thrive at school. Now its ambition is also to lead the way on dyslexia.

Video: Watch how the Hanne-project became the starting point for the world’s first dyslexia-friendly workplace.

Tests

“My workplace used to be the world’s best,” says Sandal, who started at the plant 25 years ago. “Do the job, produce nickel and try to pass the internal tests.

“Until, that is, the office staff decided we also had to fill out forms. That’s when my little secret came to light – I couldn’t write.”

He managed initially by faking and copying. But as the number of written manuals, forms and safety procedures grew, his frustration increased and he was constantly in opposition to management.

“In my eyes, that lot were my enemy,” Sandal says. “They destroyed my working life. I could do the job, I was good at it. And they ruined it. I was unhappy at work, there was constant pressure, and I tried to hide away as much as possible.”

He received good support at home from his wife, but life at work became too difficult when HSE vice president Harald Eik wanted to introduce yet another form. Over dinner, he told his family that he couldn’t cope any more.

“I can’t fill out the new form,” he complained.

“They won’t understand my handwriting, they’ll start laughing at me again. I can’t stand it.”

Hanne then spoke up: “But, Dad, if the vice president doesn’t know, he obviously can’t do anything.”

Confrontation

Eik had no idea that Sandal had faced difficulties with writing since his childhood. “I was going to introduce a new form for personal safe job analysis, and therefore went round to all the safety meetings,” he recalls.

When the turn came to the nickel service department, he found himself confronted by a furious Sandal – who felt he was being driven out of work.

“Why can’t I take part?” he asked. “Why am I being excluded?”

Sandal expected an escalation of his conflict with management, but Eik met his anger with curiosity and wanted to know more about what this meant and how the problems could be overcome.

That marked the start of the Hanna project – named after Sandal’s daughter – at the nickel works.

“I realised that, as head of HSE, I’d undermined Roald’s professional pride,” admits Eik.

“He knew his job, but couldn’t fill out the forms. A lot of people here are good at their job, but that’s not because we’ve written good procedures.

“We’re an industrial workplace which brings together people with intelligent hands. They’re good workers, and we must customise for them. We’re going to be a workplace where everyone is taken seriously.”

Openness

When the project began in 2019, Eik imagined that it would primarily concern digitalisation and technical solutions.

“But I learned that this is first and foremost about openness and expunging the shame. Then it’s important to learn what dyslexia actually involves.”

The first step was for Sandal to take Magnussen, his good friend and colleague, on a tour of all the departments to talk about their challenges.

“I’ve got the same problem myself, except that my difficulty is with reading,” says Magnussen.

“But I felt it was incredibly embarrassing and painful to go round and tell people about this. Fortunately, we were met with sympathy and understanding.”

He found his own motivation in many years of frustration over how little the trade exams were customised for dyslexia sufferers. Always failing these tests meant he never got a pay increase.

His goal now was to do something for the young people coming after him.

Magazine

“The other step we took was to produce a magazine which was sent home to all our employees in order to emphasise that we considered this important,” says Eik.

Plans called for managers to learn about the issue at a collective gathering.

That approach was scuppered by Covid, so the courses had to be run in several rounds limited to seven participants at a time.

That proved important. At every session, somebody raised a hand to open up about reading and writing difficulties – either their own or among family and close friends.

“All credit is due to Roald and Arild for taking the lead and being the first two who dared to breach the taboo around this subject,” says Eik.

“Today we know that at least 10 per cent of our personnel face one challenge or another with reading and writing.”

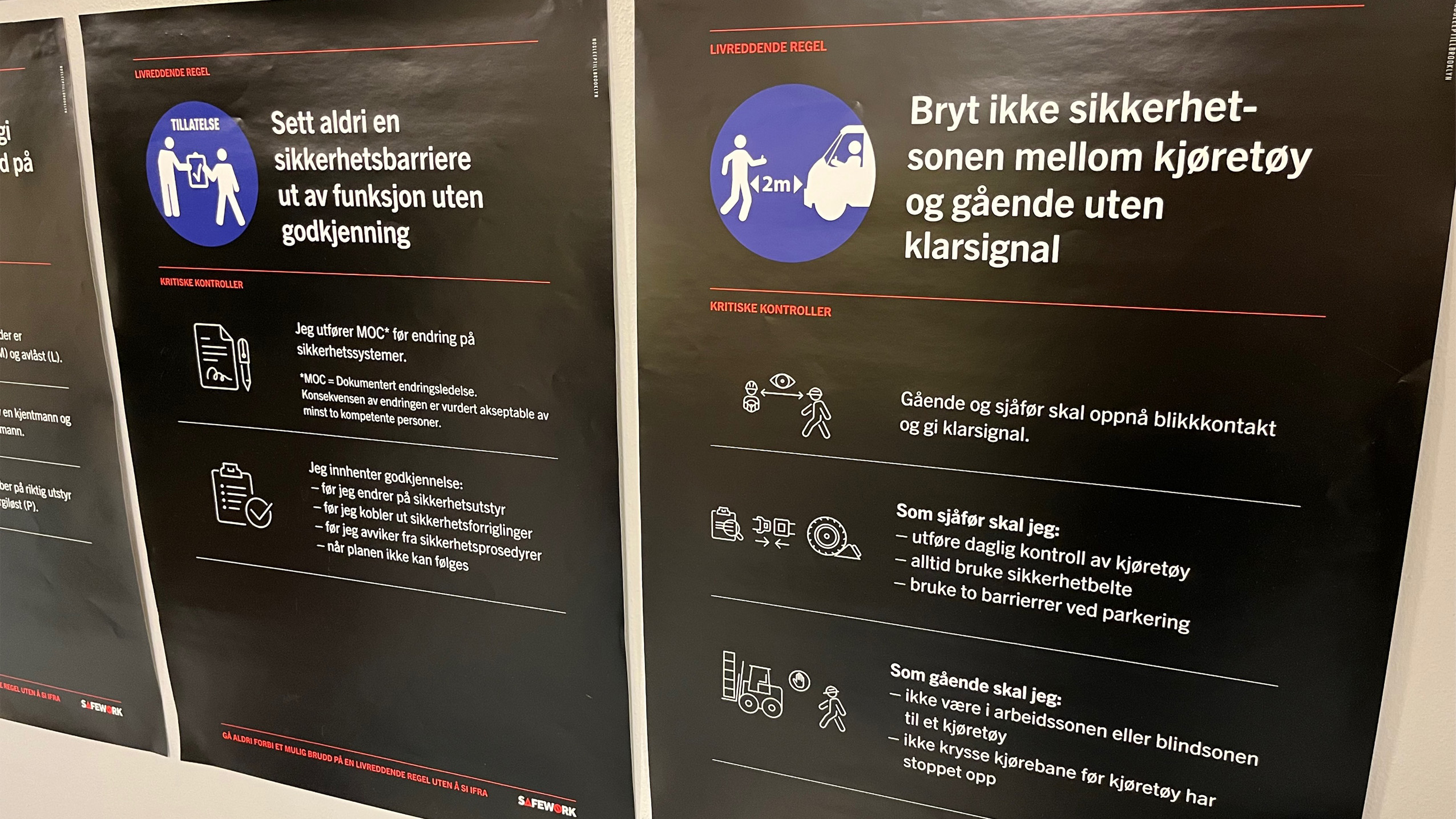

Since then, the company has done a lot to simplify communication. Text in procedures has become shorter and clearer, for example, with descriptive illustrations. And internal tests can now be taken orally.

Morning meetings in all departments now have an oral review, rather than passing out the information in writing. Supervisors also know who can benefit from an extra run-through afterwards.

“We’re not out to change people with dyslexia,” emphasises Eik. “We’re the ones who’ll be altering the way we customise work.”

He is full of praise for union officials, who have played a unifying role with everyone working on the project.

“We’d never have got anywhere without their commitment,” he emphasises.

Room

Alexander Andersen, chief shop steward for the Norwegian Union of Industry and Energy Workers at Glencore, notes that there was still room for industrial workers with various challenges until well into the 2000s.

However, today’s growing demands for documentation are helping to leave many otherwise handy people behind.

“The work Roald and Arild started here represents a big step towards Norwegian industry taking back the social responsibility it used to have,” Andersen says.

Eik agrees. “There’s no mismatch between strategic goals and what must be done to ensure that everyone thrives at work,” he says.

“Now that we know how to reach those with reading or writing difficulties, life’s got easier for everyone. The benefit is a safe and attractive workplace with stable production.”

Commoner

“Issues with reading, writing, maths and language are commoner than most people think,” says project manager Magnvor Lunåshaug at the Dyslexia Norway society.

“It’s estimated that 40 per cent of the population suffers from such challenges to a greater or lesser extent, and 10 per cent have more serious and lasting difficulties.

“Unfortunately, this subject is very taboo for many people. Some sufferers have never told anyone else about it, either at home or in the workplace.”

Her organisation works to spread information about both problems and strengths, and to make people understand that dyslexia does not reflect any lack of intelligence.

“Customising the working day, providing access to the right aids, is important,” she says.

“Where industry is concerned, these difficulties can represent a safety risk because employees may have problems understanding or communicating both orally and in writing.”

She emphasises that dyslexia is found among all types of employees, doing both practical and administrative jobs, and regardless of title and role.

“In today’s society, with its masses of information, knowledge about and customisation for everyone with such challenges can help to enhance mastery of tasks and increase acceptance. That in turn makes it more secure for them to be open about their position.”

Dyslexia

- The word means quite simply “difficulties with words”.

- It covers problems with learning letters and distinguishing them from each other.

- Several forms have been identified, with varying seriousness.

- Dyslexia is an innate, heritable condition and does not reflect lack of ability or poor teaching.

Meant much

For process operator Lena Gjødestøl at Glencore, the customisation process has meant much. She is herself dyslexic, and chose to be open about it when arriving as an apprentice eight years ago.

“I found reading handbooks heavy going,” she says. “But I’ve received a lot of help from colleagues who read things for me, look through what I’ve written and correct mistakes.”

She has taken over as head of the Hanne project, ensuring that the pressure is being kept up on the measures implemented and planned.

A number of digital aids have already been developed, including a personal safety form for mobile phones which reads the text to the user. It can be completed by speaking the entries.

“I’m also keen to develop videos which show how work operations should be carried out,” Gjødestøl reports. “Scanning a QR code on a machine, for example, will bring up a video which shows what valves and positions are to be used.”

She has the following advice for dyslexics:

“First and foremost, you must be open about it. If the company doesn’t know you need customisation, it’s difficult. And then it’s only a matter of starting at one end, working with simplified texts and making things more oral.”

Results

Night has fallen when Sandal and Magnussen stroll over the zebra stripes and out of the main gate. Many years of fighting over the issue have brought results, but also cost a lot of energy.

“My ship has sailed,” admits Sandal. “I’ll get no education. What means something for me now is that young dyslexics see a future where there can get help to learn without obstacles. Then I’ll know we’ve succeeded.”

The biggest gain is that the number of dyslexics taking their trade certificate at Glencore has risen sharply.

“The days when people thought we were stupid or backward have gone,” Sandal says.

Oil sector following suit

The dyslexia project at Glencore Nikkelverk has had spinoffs, and the petroleum industry is also aiming to get better at customising for employees with reading and writing difficulties.

A pilot project on a dyslexia-friendly workplace was launched this year by the Federation of Norwegian Industries (NI), the Norwegian Union of Industry and Energy Workers (Industry Energy) and Dyslexia Norway.

Supported by the IA industry programme for oil and gas suppliers, it seeks to make companies a better place to work for all employees.

“Such a project has great significance for our members, since many workplaces out there experience these challenges,” says Frode Alfheim, president of Industry Energy.

“It’ll ensure that personnel in the industry have an even more secure and inclusive workplace. That’s important both for those at work today and for new recruits to the sector.”

He is supported by NI managing director Stein Lier-Hansen:

“It is important for employers to make provision for all their personnel.

“Customising strengthens HSE work and can contribute to preventing accidents, enhancing efficiency and reducing sickness absence.”

The following companies are involved in the pilot project:

- Glencore Nikkelverk, Kristiansand

- Ineos Rafnes, Bamble

- ESS Support Services AS, Stavanger

- Aibel AS

- STS Gruppen AS, Bergen

- Aker Solutions AS, Egersund

- Coor, Bergen

- TechnipFMC, Ågotnes