Process for better risk management

Norway’s petroleum industry has got steadily better over the past 20 years at managing important factors which influence risk, thanks to data provided by the RNNP.

Photo: Anne Lise Norheim

Photo: Anne Lise Norheim

Photo: Anne Lise Norheim

Photo: Anne Lise Norheim

- RNNP

- Risk management

Variations

Breaking down the information to facility or plant level, however, shows big variations between players and over time. Some reveal signs of a wide gap compared with comparable facilities/ plants.

But Torleif Husebø, who has led the RNNP process at the PSA over many years, is nevertheless cautious in attributing this trend to the project’s findings.

“It hasn’t contributed in itself to reducing risk,” he points out.

“That job has been done by the industry and the parties involved in it.

“The most important role of the RNNP has been to provide companies, unions and government with a common platform for discussions on safety trends.

It’s also helped to identify HSE-related challenges at sector level.”

Entrenched

Husebø points out that the RNNP is entrenched in the Safety Forum, the key arena for HSE in Norway’s petroleum industry. Its members always get to see and discuss the report’s findings on the basis of the updated picture these provide.

The RNNP describes the status, and provides the basis for joint discussions between the parties on new initiatives.

“This process has helped to identify and illuminate challenges and to create agreement between the parties on priorities, initiatives and measures to improve safety,” says Husebø.

A positive trend over 20 years indicates both that we have a regime which functions and that we have an industry which gets to grips with the challenges. “At the same time, we know that safety is a ‘perishable commodity’. We must always look ahead and remember that history gives us no guarantees about the future.

A good example he cites is industry efforts to cut hydrocarbon leaks and well-control incidents.

The process has also provided valuable insights into the industry’s work in other risk areas, such as maintaining and managing barriers.

“So the RNNP has supplied information and knowledge and has been part of the process for understanding the position and being able to work purposefully on risk reduction,” Husebø says.

Priorities

Where the government is concerned, the RNNP provides an important basis for setting technical priorities, planning and implementing audits and other activities.

Signals from the PSA to the industry about necessary improvement measures often take their starting point from the report’s figures.

“The RNNP is primarily a trend tool,” explains Husebø.

“It takes a retrospective look and helps us to see things over a long period.

“Annual variations will always occur, and we are therefore cautious in using the results in an overly specific way. Their big value lies first and foremost in painting the long-term picture.

“A positive trend over 20 years indicates both that we have a regime which functions and that we have an industry which gets to grips with the challenges.

“At the same time, we know that safety is a ‘perishable commodity’. We must always look ahead and remember that history gives us no guarantees about the future.”

Crucial

Quality assurance of the figures has been a crucial factor in generating agreement over the RNNP results, Husebø points out.

“A goal for the process throughout has been to concentrate attention primarily on the results. We’ve largely succeeded with that so far.

“We achieve this by devoting substantial resources, both internally at the PSA and out in the industry, to checking the quality of the information included in the RNNP.”

An in-depth study has been conducted for the 2021 report to assess the extent of erroneous and inadequate reporting to the RNNP, Husebø reports.

“The results strengthen our belief that underreporting to the process isn’t so great that it affects the conclusions.”

But he says it is important to note that the quality of the RNNP figures rests entirely on the industry reporting the information it is supposed to.

“The RNNP is part of our interparty collaboration. The parties themselves have a collective responsibility for making this work. That applies to reporting and quality assurance of the information – and not least to the use of the results.”

Aiming to make people safer

Personal injuries in the Norwegianpetroleum sector were relatively numerous in the 1990s. But a fixation by companies on lost-time incidents (LTIs) created a distorted picture of reality.

Before the RNNP, industry players were largely concerned to count harm suffered by people who had to take time off work as a result.

These LTIs were used as an indicator, especially with contractors, and were easy to manipulate, says Øyvind Lauridsen, who has played a key role in the PSA’s RNNP work from the start.

“During the 1990s, we saw company figures for such LTIs fall sharply and actually get close to zero towards 2000. That looked great on paper, but the reality was unfortunately very different.”

The truth was that the number of incidents involving harm to individuals was relatively high during the decade, with far more serious injuries and fatalities than today.

Robust

One aim of establishing the RNNP was to obtain more robust reporting and sounder figures on the risk of suffering harm. Rather than counting LTIs, the statistics were based on the definition of serious personal injuries in the regulations.

“With the RNNP, we’ve shifted industry attention away from LTIs and over to serious injuries,” says Lauridsen.

“That made it clear there were far too many of them, and that the companies had to get them down.”

The RNNP gave us a better measurement tool, both sides in the industry trusted the figures presented, and we therefore spent less time arguing over the numbers.

Accountable

Active use was made of the personal injury statistics to emphasise company responsibility and to achieve a positive trend, he explains.

“The RNNP gave us a better measurement tool, both sides in the industry trusted the figures presented, and we therefore spent less time arguing over the numbers.

Instead, the companies devoted their time to identifying measures which gave results. Looking back two decades later, the figures show a positive trend for serious personal injuries and fatalities throughout these years.

“The improvement has been marked. We were down to 0.6 serious personal injuries per million hours worked in 2020, compared with 2.3 in 2000.

That’s a sharp reduction.”

Pushing to curb escapes

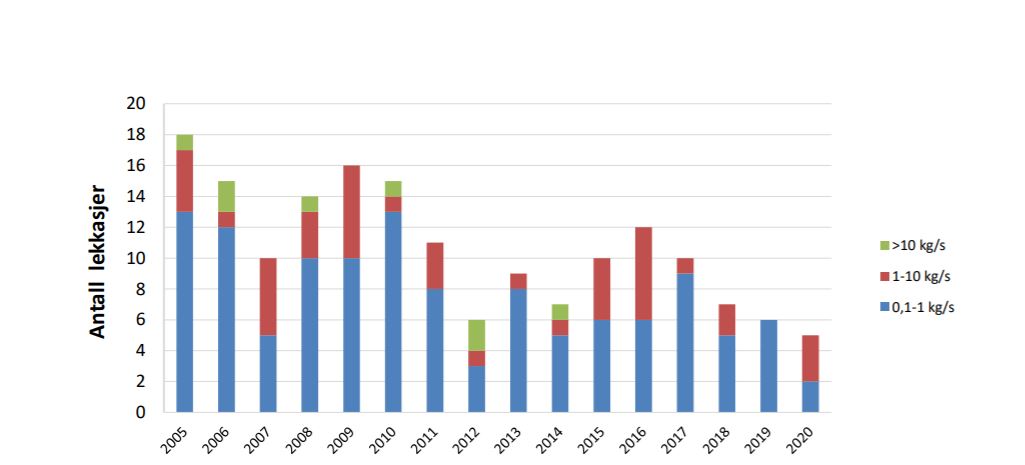

Purposeful and long-term work has allowed Norway’s petroleum industry to achieve a sharp decline in hydrocarbon leaks. The results of this drive show up clearly in the RNNP.

Putting a stop to escaping gas or oil was identified in the early 2000s as a key objective for lowering the risk of major accidents in the Norwegian offshore sector.

Forty-three such incidents exceeding 0.1 kilograms per second were recorded on the NCS in 2000, prompting the Norwegian Oil and Gas Association and the operator companies to launch a gas leak reduction project from 2003 to 2007.

One of a number of projects and activities aimed at overcoming the problem, this identified a need for greater expertise about conditions relevant to prevention, says Knut Thorvaldsen, deputy director general of Norwegian Oil and Gas.

The number of leaks above 0.1 kg/s was down to 10 by 2007. Once the project had ended, however, developments began to move in the wrong direction and 16 incidents were recorded in 2009.

Project

In 2011, therefore, Norwegian Oil and Gas launched its hydrocarbon (HC) leak project.

“We analysed the incidents which had occurred in order to identify their causes, and to understand where measures should be applied,” Thorvaldsen reports.

This analysis showed that more than 60 per cent of the leaks had arisen in connection with work on hydrocarbon-bearing equipment in the production phase.

The next step was to establish how planning and execution of activities involving piping systems could be improved, and guidelines on this were produced.

“We analysed the incidents which had occurred in order to identify their causes, and to understand where measures should be applied,” Thorvaldsen reports.

Since 2013, the industry has issued fact sheets on oil and gas leaks larger than 0.1 kg/s on the NCS. They provide anonymised descriptions of incidents, including an overview of causes.

Also including lessons learnt from internal investigations by the companies, these studies are now due to published with a new searchable user interface on the Norwegian Oil and Gas website.

Transfer

The 2018 White Paper on HSE in the petroleum industry identified a need for better experience transfer after incidents, and the Safety Forum was mandated to look more closely at how the industry could improve.

Several reports were published in 2019, including one on learning from incidents. According to Thorvaldsen, this document was followed up in various industry fora. The latest figures from the RNNP show five hydrocarbon leaks on the NCS in 2020 – a very considerable improvement on the figures from 20 years ago.

Thorvaldsen acknowledges that the long-term trend is positive. But he says management and employees in each company must continue to pay great attention to this issue if major accidents caused by hydrocarbon leaks are to be avoided.

He emphasises that the annual RNNP reports are very important for the industry:

“They provide a unified picture of HSE conditions on the NCS.

“We use the data actively and adopt measures where they’ll have the greatest effect. The ambition is continuous HSE improvement.”

Doing well

Systematic efforts, with the emphasis on learning and experience transfer, have helped to reduce the number of well-control incidents on the NCS.

Ten events of this kind were experienced in Norway’s offshore sector during 2020 – the lowest figure since records began two decades ago.

All incidents were moreover classified as “green” – in other words, a regular occurrence where the operator recovers control of the well with the aid of standard procedures.

“The data we have from 2010-20 are very much better than those for the previous decade,” says Monica Ovesen, discipline manager for drilling and well at the PSA.

Macondo

She explains this trend as an indirect result of the Macondo blowout in the Gulf of Mexico in April 2010, which focused much greater government and industry attention on well control.

While incidents were previously rated as either serious or non-serious, “ownership” of the categories was transferred from the PSA to the Norwegian Oil and Gas Association.

The latter produced a separate guideline in 2011 on classifying well incidents, introducing a more fine-meshed system utilising four levels of seriousness categorised by colour.

“Our main impression of the industry is that it works well,” says Ovesen, who is also the PSA’s observer at the Drilling Managers Forum (DMF).

“Operators in Norway share an exceptional amount of information with each other, and that’s not usual in international terms.”

The DMF brings together drilling and well specialists from 29 operator companies, plus stateowned Petoro, once a month to review and discuss all well-control incidents on the NCS.

In the wake of Macondo, operator companies and members of the Norwegian Shipowners Association also established the Well Incident Task Force.

This group is responsible for producing “learning packs” about incidents with a big potential for offering lessons. These are open to all on the Norwegian Oil and Gas website.

Culture

Ovesen believes that culture plays a big part in this area, and that the oil industry in Norway is more concerned to avoid accidents than to conceal errors.

Tove Rørhuus, manager for drilling and well at Norwegian Oil and Gas, agrees with that impression:

“If one fails, everyone fails. A serious incident on the NCS would hit the whole industry.”

In her view, experience transfer and information sharing in the industry make a positive contribution to progress.

The learning packs have been reviewed by offshore drilling contractors, and are also used by educational institutions for teaching and training on well control.

If one fails, everyone fails. A serious incident on the NCS would hit the whole industry.

“There’s actually also demand internationally, and the packs can naturally be freely used and shared,” Rørhuus reports.

Ovesen notes that several serious incidents have occurred since 2000, including gas blowouts on Snorre A in 2004, Gullfaks in 2010 and Troll in 2016. These three were very different.

“No matter how much we analyse the data, we can’t predict when and how an incident can occur,” she adds. That explains why giving more attention to prevention and reducing risk are important.

Discharging a duty of care

Risk management is about preventing a spectrum of incidents. Facts about acute discharges to the sea make an important contribution to this work.

The PSA has issued a report on trends in risk level in the petroleum activity - acute spills (or RNNP AU) every autumn since 2010. This combines discharge data with the fact base in the rest of the RNNP, and assesses events which have or could have caused acute pollution.

In addition to crude oil, the report covers spills of other oils and chemicals and from the injection of drill cuttings.

It includes analyses of trends for incidents with a major accident potential – capable of causing loss of life, acute pollution and/or loss of material assets if several barriers fail.

The development potential with regard to oil pollution is assessed as part of the work.

“The industry must take an integrated approach to preventing harm to people, the natural environment and material assets,” explains Finn Carlsen, director of professional competence at the PSA.

“The RNNP AU contributes to that, since it analyses the same base facts, data, DSHAs and barriers as the rest of the RNNP – with the natural environment as its starting point.”

He emphasises that all types of incidents must be investigated in order to make sure that weak signals are picked up.

“When something happens, it’s important to establish why the barriers intended to prevent it have failed.

That applies whether the incident has consequences for people, the environment or material assets.

“Complete barriers are a basic safety requirement.”