Contractor and collaborator

Photo: Monica Larsen

Photo: Monica Larsen

Photo: Jonas Haarr Friestad

Photo: Jonas Haarr Friestad

New forms of contract are emerging in the oil sector, where the concept of “one team” has also been spreading. The question is how these work in practice.

The PSA’s main issue for 2021 is "side by side with the suppliers". In a series of articles and reports, we explain the background for this main issue and examine the role played by the suppliers in the petroleum industry.

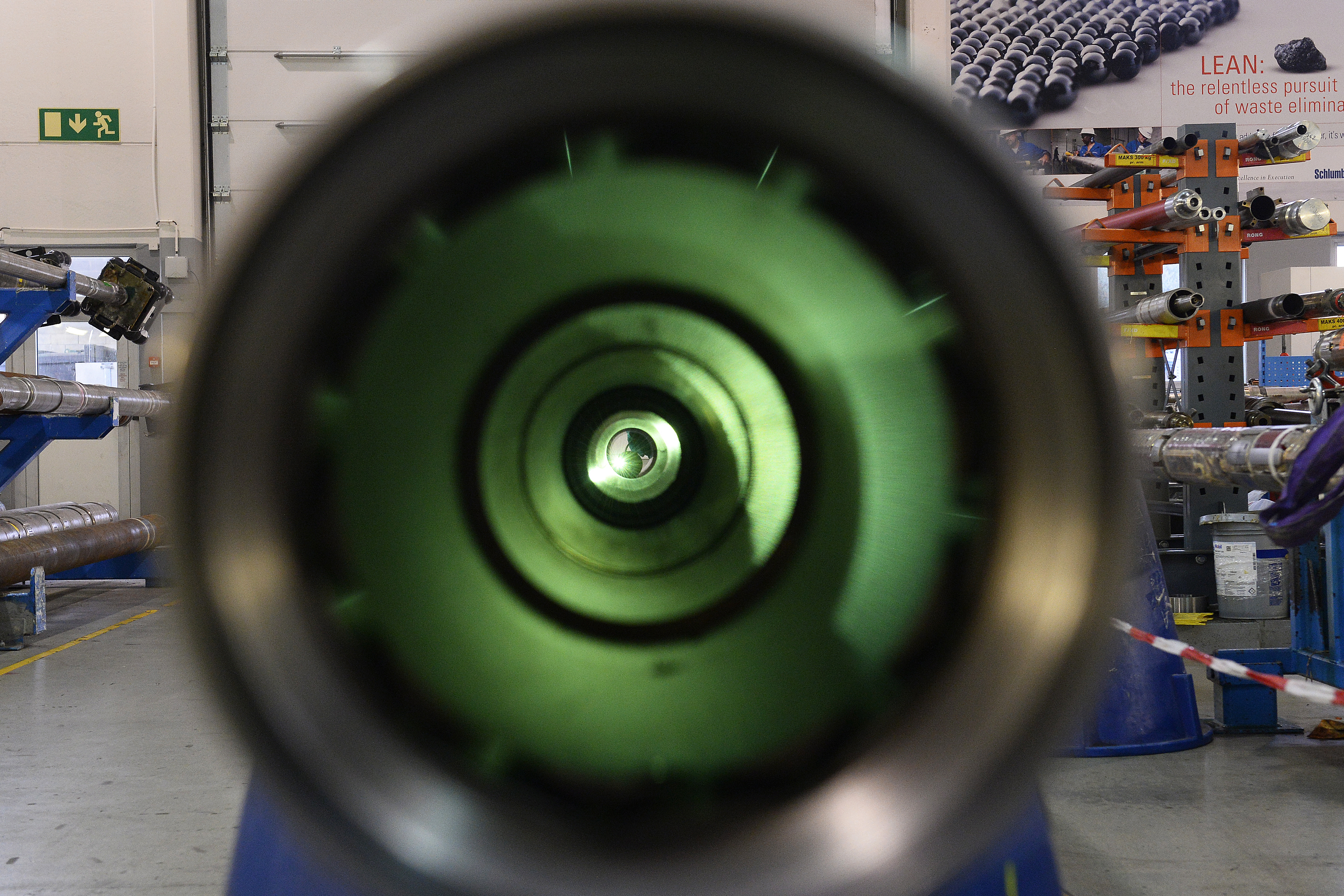

Workshops for servicing and repairing drill pipe and other items stand one after another on the big Schlumberger site at Tananger west of Stavanger.

Starting with washing and cleaning in the first shop, equipment progresses through repair, calibration and testing until it is ready for dispatch from other end.

“We save half an hour by attaching the drill bit to the string here,” explains workshop head Terje Nordhus. “More and more equipment is being readied on land before going offshore, where it can just be plugged in and started up.”

The desire to achieve the best possible well position for recovering the maximum amount of oil and gas means the drill string is packed with advanced electronic devices.

These measure, log and transmit information from the borehole to a directional driller and other specialists – who might well be controlling the operation from land.

The lowest section of a drill string may contain 30-100 metres of measuring equipment, Nordhus explains. He pats a seven-metre length of pipe and puts its value at roughly USD 500 000.

“We’re measured on efficiency and downtime, both in our own company and by the customer,” he explains.

Twice as fast

“Technological improvements and alternative ways of working introduced since 2014 mean we now drill twice as fast in terms of metres per day,” says Sigbjørn Lundal.

He serves as the coordinating chief safety delegate in Schlumberger Norge, and backs this comment with figures from Equinor.

In 2007, the Norwegian oil company drilled an average of 76 metres per day on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS). That has risen to 147-157 metres by 2020.

Lundal says that the formidable improvement in efficiency achieved in this sector has resulted in more offshore projects going ahead.

“The trend is very positive for oil company finances. But it also means that our employees working out there have a busier time than before – with fewer resources.

“While Schlumberger earlier had 12-14 people to operate the drilling and logging equipment on a platform, that figure is now down to five.

“And while the personnel used to be specialists in their particular discipline, every employee has now had to learn to do several types of job.

“The service companies themselves were also more specialised. Some were good at cementing, others at drilling. Most have now abandoned that and become turnkey suppliers.”

Bonuses

While the normal practice in the past was to agree a fixed price for the number of metres drilled, payment today depends more usually on bonuses for the work done.

One customer tried to relate such bonuses to HSE incidents, so that the supplier suffered financially if injuries were incurred along the way.

But such a system encourages under-reporting of incidents, which Lundal says is extremely harmful and threatens the whole Norwegian HSE regime.

“This attempt was averted by our safety delegates and unions, in collaboration with their counterparts in Baker Hughes and Halliburton,” he explains.

“We face the same challenges where efficiency improvements are concerned, of course, and meet the same customers demands. Even though we’re competitors, we stand together on the challenges.”

Relationship

Another trend witnessed by Lundal in recent years is the adoption by customers of the “one team” concept to describe their relationship with suppliers.

“But this in no way means the same thing for all operators,” he observes. “If one of them isn’t interested in having us totally integrated in it’s organisation, it doesn’t have ‘one team’.”

He cites Aker BP and Hungarian company MOL as examples of customers who have understood how this should be done.

The first of these entered into an alliance with Schlumberger and Stimwell Services a little over a year ago. This aimed to achieve faster operations and more oil production with the aid of well intervention and stimulation.

“These operations are so complex that good collaboration is essential, or this wouldn’t have functioned,” emphasises Lundal, who says the model works.

Schlumberger personnel are involved in planning the solutions they will be delivering, and deciding how much input they should have. The working environment is good, with low sickness absence.

Operator

When the economic slump hit the oil sector in 2014, Karl Johnny Hersvik was CEO of Det Norske Oljeselskap (Det Norske), operator of the Alvheim field in the North Sea.

This was to be developed with several subsea wells tied back to a production ship, and Det Norske decided to try out a simpler and more efficient organisation.

Instead of separate project teams at the operator and the contractor, with a joint group at the top, it built a single team with a unified management.

“Det Norske basically believed it was fairly good at implementing such projects,” says Hersvik. But the results astonished the company.

It not only succeeded in cutting development costs by almost 20 per cent but also – and most extraordinarily – reduced execution time.

“We were used to this work taking 20-22 months,” Hersvik explains. “But the alliance project – the whole Alvheim subsea tie-back – was done in 11 months.”

Alliances

Hersvik is today CEO of Aker BP, which currently has seven alliances of this kind covering various areas of its business. The best of these show a substantial improvement in quality.

However, Hersvik admits that this way of working can be “a bit of a troublesome process viewed from a management perspective. At one point, you begin to wonder if you’ve lost control.

“And then you discover that the opposite is happening – you’ve got better control. It’s just that part of the problem-solving has moved closer to the problem.”

He adds that companies in Norway have a huge advantage – a performance-based regulatory regime. “That means there are many ways of solving problems.”

According to Hersvik, the better the assignments are defined and structured, the more successful the alliances have been. But there is one exception.

This is the well maintenance and intervention partnership with Schlumberger and Stimwell, where it has proved possible to build in a single solution and collaborate well despite big variations in the scope of work.

Hersvik emphasises that trust between the partners is essential for alliance success. “And one more thing – we as an oil company must accept that the suppliers have to make money.”

He sometimes finds an attitude among operators that their suppliers should be squeezed to the limit, and regards that as a very counterproductive approach.

In his view, enough wastage exists in oil and gas processes for all the players to make a good living if they work systematically on eliminating bureaucracy and duplication.

“We want our alliance partners to earn well and be successful commercially when we succeed as an oil company,” Hersvik says.

Share

That point is also made by PSA principal engineer Irene B Dahle, who believes that sharing both upside and downside in financial terms is a precondition for working as a team.

“The main challenge I see with ‘one team’ is that it can quickly become fine words,” she says. “You must have incentives, including in the contract, which support such collaboration.

“Costs are under pressure in the industry. So the search is on for new models to make work more efficient. If you can then get better collaboration and safety as well, nothing could be better.”

But if the model means that the financial risk is transferred from the operator to the supplier, she observes, it can have unfortunate consequences.

“The supplier risks losing money, and that can hit safety. Unfortunately, we sometimes see that the contracts are very tight – and very much on the operator’s terms. That’s a concern for us at the PSA.”

Read more: Supplying safer outcomes

-

Supplying safer outcomesThe PSA’s main issue for 2021 emphasises the great significance of the supplier companies for safety in Norway’s petroleum industry.

-

One team, shared responsibilityEach company has an independent responsibility for safety, but the operators must make it possible for suppliers to work safely in a good manner.

-

Surviving at the sharp endInsulation, scaffolding and surface treatment (ISS) companies are among the first to feel the effect of cut-backs and cost savings. So a long-term contract is worth its weight in gold.